Originally from North Carolina, Chip moved to the Navajo reservation in 1987 after medical school to work as a doctor for the Indian Health Service. He planned to stay on the reservation for only a few years but his love for the place and the people, along with a commitment to service, have inspired him to reside there for over 25 years. If you have driven along Arizona highway 89 anytime over the past several years, you may have seen his artwork – mural-sized photographs of the Navajo people posted on various sites, including the sides of old buildings, water tanks, and road-side stands. Chip posted the first images anonymously in 2009. In 2014, his efforts became more official when he formed The Painted Desert Project. He invited street artists from around the world to engage with the community and create murals on reservation land.

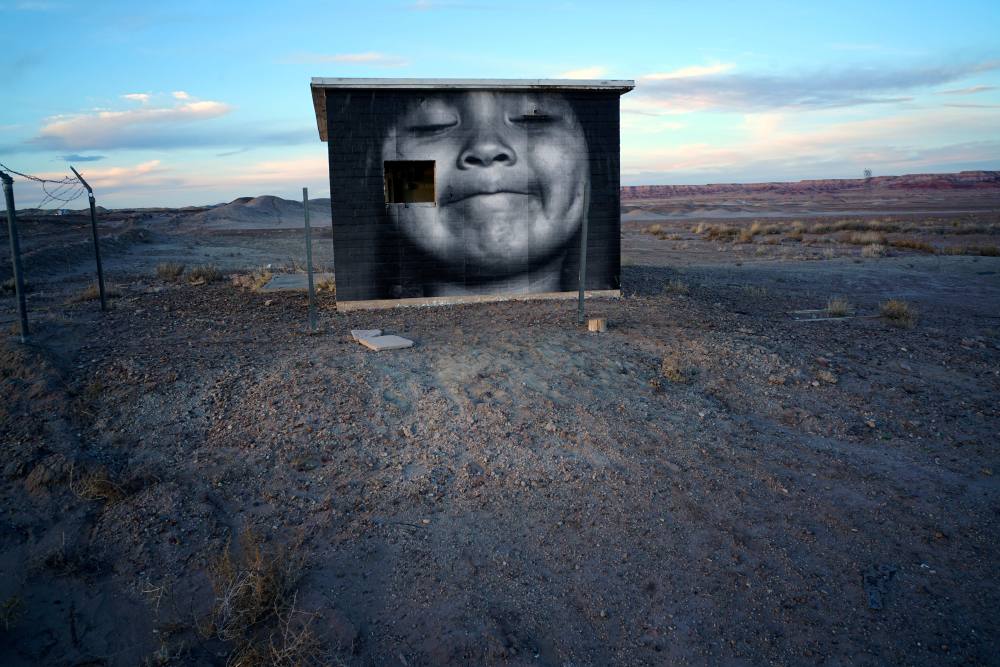

Image from the Navajo Nation © Chip Thomas

Here is a condensed version of a conversation between SEE and Chip Thomas:

SEE: Could you talk a bit about how your images on the reservation come about?

CT: My photography with people here on the reservation generally stems from my work as a doctor in the clinic. It frequently starts with me meeting someone who interests me in some way. It could be their lifestyle – for example, they’re still moving sheep between a summer camp and a winter camp -- or they represent the culture in a very beautiful and traditional way in how they dress. A lot of times it actually starts with me asking, ‘Can I come to your home and hang out with you? I’m interested in taking photographs and documenting your day-to-day life.’

SEE: And it seems like a lot of the photographs are fairly organic. Although some of your photos are, I would say, portraits.

CT: That’s actually happened since I started doing this project. If you look at my earlier work, there’s very little portraiture. But for this project [large images along the roadside] I want the images to register quickly, because my audience now is traveling in cars passing by at 70 mph. So, there’s a lot more emphasis on faces. I’ve been shooting more portraits since 2009 than I ever did before. But I still enjoy going out in the field and shooting in a documentary style.

Image from the Navajo Nation © Chip Thomas

SEE: When you do these portraits for the large prints are you posing people?

CT: I don’t pose people. I do try to get them in the best light. So, maybe I’ll ask someone to stand in a doorway. But by and large, I do try to photograph them as I can find them.

SEE: What reactions do people have when they see their faces on such a large scale?

CT: It depends on the age of the person being photographed. For example, there’s a woman who is an elder in the community. She’s probably in her seventies, a traditional Navajo female, who dresses in that way. I really wanted to capture that on film. There are water tanks in the community of Grey Mountain about 40 miles north of Flagstaff. There are four abandoned tanks there. The tanks are about 16 feet tall and they are curvilinear structures. I could put a face on that structure that’s 16 feet tall, but it would be tricky to read the image because it would be wrapping around the tank. I include her hands and her bracelets in the image of her on the tank. It goes from about her waist to the top of her head, 16 feet tall. Her comment was, ‘Oh, I didn’t realize it was going to be that big!’

Everybody loves it and it’s a beautiful image of her and her jewelry and she’s smiling. It’s a nice portrait. But there’s still a feeling on the reservation that self-aggrandizing behavior should be discouraged. Therefore, a part of what I’m doing is in conflict with that attitude.

But I feel better about what I’m doing now than when I was doing gallery shows because – and this is where I talk about the integrity of the work - I have to be responsible. I mean, now that people can see what I do with their photographs, I’m pretty clear to them about my intentions before putting something up.

Image from the Navajo Nation © Chip Thomas

SEE: Could you tell us the story behind this project? What ideas or circumstances got you started?

CT: Every five years I would take a sabbatical. The first sabbatical I did after coming through this intense period was in 2009. I spent three months in Brazil. I went there with the thought that it might be a place I would consider living part-time at some point in my life. I was studying Portuguese, I was photographing, and I was studying an instrument that I’ve been playing for a while called the pandeiro.

For the two months I’d been in Brazil, I’d seen a lot of graffiti and street art all over Brazil. It’s actually known for the quality of its street art. It was interesting because as I was learning Portuguese, I was having trouble navigating the city and it was the street art that was helping me navigate. If I recognized a piece, I knew where I was in the city, relative to my home or to where I was going. I’ve always had an interest in street art so wherever I would go, not just in Brazil but in Europe and other countries, I would notice art on the street.

I moved into a studio apartment and, as is turned out, there was an artist on the ground floor whose work I’d been seeing pretty much everywhere for the two months I’d been there. He was a street artist who was Brazilian who didn’t speak a lot of English. His studio was a very open space and there were a lot of artists, some from Brazil and others from Europe, who would congregate in his studio every day. They would share ideas and their sketchbooks, as well as look at other people’s work on the Internet. For three weeks I was in the space every day. They didn’t care that I was this older, black guy just hanging out. They just had a love for what they were doing and they loved sharing ideas and they would let me go out on the street with them as they were doing work.

As I was about to leave Brazil, I think on a website, I saw work by the French artist, J.R, who did an installation in Rio in 2009. It was the most dramatic, amazing thing I had ever seen. It was also the first time I saw how a photograph could be used as a medium of street art.

SEE: That sounds like a pivotal point in your career. You’re doing all these unconnected things like being a doctor and a photographer. It’s amazing that you were able to weave those things together while you were on an extended leave.

CT: It was amazing! Because frequently when I travel I’m looking for an epiphany. On this trip, I had just come through an intense period and I was really into just chilling out – studying Portuguese, studying an instrument, spending quality time at the ocean and photographing.

When I came back to the reservation, I had such a strong feeling of happiness, having had the opportunity to spend time with these guys for three weeks. I wrote to JR and asked him if he would be interested in coming to Arizona to do a project similar to the one in Rio. He did a fascinating one in Kenya, as well. He’s worked all over the world.

He never wrote back to me. However, during the three weeks that I was waiting for him to respond -- as I was driving around the reservations on roads I had been driving for the last 22 years -- I was suddenly asking myself, “If JR were to come do a project here, where would he put his pieces? How would he engage the community?

Image from the Navajo Nation © Chip Thomas

Image from the Navajo Nation © Chip Thomas

Every time I was out driving I noticed interesting places to put a piece up. After not hearing from him for three weeks, I just went to Kinkos one day. I took a 4 inch x 6 inch photograph and said, “I want you to blow this up to 4 feet x 6 feet.” They just looked at me like I was insane. I didn’t know anything about the process of tiling and I just assumed that big photographs came off in one big piece of paper. I was really starting from the ground floor. The only thing I knew was that Shepard Fairey printed his own work at Kinkos. I looked up a recipe for wheat paste on the internet. I went out at night -- not necessarily engaging the owner of the structures along the roadside -- and put up my photographs. I was doing it surreptitiously. Things changed a bit about 6 weeks after putting up my first piece. In June 2009, I put a photograph of code talkers on a road-side stand that was falling down. A week later I was driving down to Flagstaff and I saw people putting the road-side stand back up. I stopped and asked if I could take a picture of the code talkers and they said, ‘You might as well. Everyone else has been stopping to take pictures of the code talkers.’

I asked them what they were doing and why they were working on the road-side stand. So this is on a road between Flagstaff and Lake Powell. It’s also the road between the South and North Rims of the Grand Canyon.

Image from the Navajo Nation © Chip Thomas

SEE: Is this State Route 89 you’re talking about?

CT: Yes, this is 89. It gets a lot of local and international tourist traffic. So many people had stopped to take pictures of the code talkers that they decided to start using that road-side stand again. I volunteered to them, ‘Well, I took the picture of the code talkers.’ The man thanked me and invited me to put another picture on the other side to stop traffic coming from Flagstaff.

SEE: Wow! Were Navajos fixing up the stand?

CT: Yes. Ninety percent, well 99% of the people who have the roadside stands are Navajo but this particular guy is actually from Mexico.

SEE: That is very interesting because it means your work was doing some kind of good in that location.

CT: Yeah. There were a couple things I realized in that moment. There was some kind of economic benefit to the community from having art on the roadside stands, so it could be a win-win situation whereby I get art up and the roadside stand owners get more traffic coming in. The other thing is that there are conversations happening between strangers inspired by the art. Hopefully connections are being made. Walls are being broken down. Stereotypes are being challenged.

SEE: So the photographs on the stands can be a positive economic effect but what about those that are randomly placed on the water tanks or run-down buildings? What would be the value to the community of something like that?

CT: Right. So, the Navajo Nation is 27,500 square miles in size. It’s home to approximately 175,000 people and there are about 200,000 Navajo people total. That means there are another 25,000 living off the rez in different parts of the world.

And, there are five natural resources here, four of which are being exploited for energy purposes -- coal, natural gas, oil and uranium. And then there’s water in aquifers, which is considered the fifth natural resource. All of those are being exploited by multinational corporations.

In that sense, the reservation is very much like a colony where its wealth is being taken off the reservation. Roughly 20 – 25 % of my patients still don’t have running water or electricity. The Navajo people should be the richest group of people living in the United States but because of the way the contracts were written for these natural resources they’re amongst the poorest. The unemployment rate hovers around 50%. The teen suicide rate is 2 – 3 times the national average. There are real issues with gang violence.

There’s not a tradition or history of social drinking here. It’s more like binge drinking, In that context, people get into altercations where they don’t know when to stop. The mortality rate from these assaults is quite high.

A month ago, there was an article in the Navajo Times that talked about the crime rate here on the reservation. There are some real challenges to living here and people in this environment do not necessarily have the best coping mechanisms. They make choices that are maladaptive, like alcohol and drugs, which leads to a high rate of domestic violence, elder abuse, child abuse, and teen suicide.

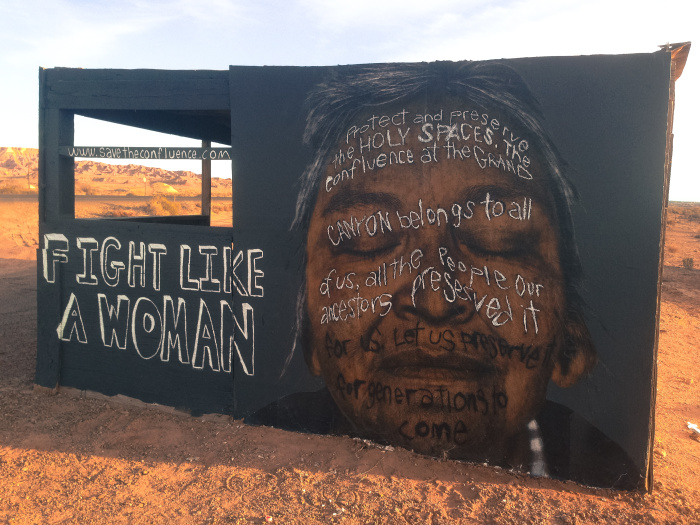

The images that I put up are my dialogue, a conversation I am having with the Navajo people, saying, “I have been here long enough to see some really beautiful and wonderful things that you all have been kind enough to share with me. I just want to reflect some of this back to you.” A lot of what I’m doing is an intentional effort.

I’ve been criticized for this. Some people want to know who am I to come in and try to instill faith and an enhanced sense of self-esteem? Well, I’m a doctor. I really see this art project as an extension of my work in the clinic where I’m attempting to help people achieve their best self and realize their dreams and goals. I see this art project as the mental health part of my medical practice.

Image from the Navajo Nation © Chip Thomas

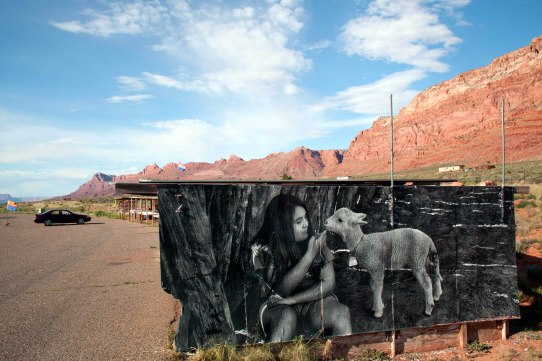

SEE: Getting back to the sheep issue - what have you seen on the reservation that shows that sheep are important?

CT: I pitched a story to National Geographic where I spent five days with a traditional family of three, moving about 250 – 300 sheep from the winter camp to the summer camp. As part of that experience, I did a lot of reading about the history of sheep on the reservation.

In the late 1800s or early 1900s, the wealth of individuals and families was determined by the size of their livestock herds. That became problematic for the tribe in that a lot of families had a large amount of sheep that were overgrazing the land. That’s when the government came in with the forced relocation program. But the traditional people used every part of the animal. So people on the reservation are known for weaving these beautiful rugs from the wool. I’ve heard hopes that the reintroduction of the Churro will stimulate a renewed interest in traditional weaving such that it could become a livelihood for some people on the reservation.

I also know that in Flagstaff there’s the local version of the Slow Food Movement. There are restaurants in Flagstaff that are affiliated with some organic sheep farms here and they’re getting lamb from the reservation.

SEE: So that’s another economic benefit of reintroducing the Churro. But are the young people on the reservation buying into this, too?

CT: Yeah, well, again, it’s not a monolithic culture. Not at all. A lot of young people on the reservation don’t speak Navajo anymore and they don’t have the same relationship with sheep and livestock as their grandparents. It’s been fascinating to be here to literally watch a culture in transition.

It’s important for places like Diné College to offer the courses that they do because it’s a re-introduction of traditional elements of culture. Actually, it’s not really a re-introduction, rather, it’s a reemphasis on traditional aspects of the culture.

Image from the Navajo Nation © Chip Thomas

SEE: Are you feeling pulled in too many directions? Personally, how is living on the reservation developing your career as an artist and your career as a doctor?

CT: Things have evolved with the art project to where there is an interesting symbiosis between my work and the art. I wouldn’t necessarily be able to take it someplace else if I were to start working in another place. I never planned to stay here this long. I thought that once my son left high school I would be free to go elsewhere. I didn’t anticipate the art taking me in this direction. That makes it incredibly satisfying.

At a point during the fall, there were a couple weeks where I was the only person working in the clinic. It’s been fascinating for me to ride this wave and just to see where we have been and where we are now. I think if I didn’t have the art project it would be very easy for me to say ‘screw this.’ It would certainly be easier for me to be in a place where I was with like-minded people. By the same token, I realize that there’s an ongoing need for health care in this community. People have a great deal of trust in me and appreciate that I’m still here after all of my friends have departed. And, like I said, I’m really enjoying what art brings to me here on the reservation.

SEE: You’ve got a really deep purpose there.

CT: Right. One of the things that struck me when I first came in 1987 was that Apartheid was still a very real thing. Nelson Mandela was still in prison. Students on college campuses were on the streets taking part in anti-apartheid demonstrations. In 1986, I was visiting a friend in Philadelphia. I went to a meeting, a gathering of elders from Big Mountain, talking about being relocated. It was the same thing that the South African government was doing with the townships, where they were demolishing them and routing people out to their homelands. The people from Big Mountain were drawing a parallel to what was happening in South Africa. I came here thinking there was solidarity amongst peoples of color only to learn that it’s not true at all.

When I did the workshop with Eugene Richards, he had you do a series of exercises. One thing we did was an interpretation of Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman. So there’s another example of a photographer doing an interpretation of poetry. He was all about looking for gestures that are universal. That’s something that’s stuck with me.

SEE: That’s interesting because I do think of lot of this gets down to the universality of humanity. What touches people, what binds them together, what can support them? And a relationship like your art and your medical work is a symbiotic one. That’s like a microcosm of the larger arena of where your photographs are going.

CT: Thanks for making that observation although it actually comes from my Quaker background in terms of consistency between one’s work and spiritual practice.

Image from the Navajo Nation © Chip Thomas